As I (Thom) was driving back and forth to teach my two classes in Colby’s JanPlan semester our fave community radio station, WERU.org / 89.9 FM, was amazing company. The trip was a hilly trek across some very snowy terrain, and somehow we just barely made it this winter without snow tires.

On one snowy commute back to Wild Air I listened to an interview with a local Maine artist, Nathan Allard. After arriving back to the cabin Sandy and I stalked him online and fell in love with his style. We connected via his Insta channel and scheduled a meeting at his gallery and home to maybe buy some art.

We dropped in on Nathan on the way back from Waterville where Sandy came along to visit the Colby Museum while I taught my last class of the semester. Just before finding the turn onto the dirt road leading down to his home, we had to stop to capture this lovely image (above) of a snowy woods sliced by an icy black stream…

At the end of the road (Sandy talking) was Nathan’s home/studio sitting right on the edge of Long Pond. This house, for many years, had been Nathan’s family camp. For those unfamiliar with local custom and nomenclature, a camp in Maine is actually a second small home that is usually in the woods, on a lake or such. A place where some people go to hunt, some to get away and be with nature. Nathan is now living there full-time and the upper floor is his studio.

A lovely young man with dark dreadlocks answered our knock. After some pleasant banter and shedding of shoes, Nathan took us upstairs to see some art in his studio. Besides the beautiful view, the studio felt primitive and earthy, neatly scatted with rocks, shells, clay pieces, wood fragments, a birds nest and, intriguingly, a mortar and pestle.

Danny Boy, portrait of the artist’s brother as a young man

One of the reason’s we were drawn to Nathan’s art was his process of painting with earth pigments so, naturally – no pun intended : ) – I wanted to know everything! Raw, found materials play an important role in his practice of egg tempera painting.

From earth-born materials to pigment for making art

He forages most of his own pigments from the woods, lake shores and rocky beaches of Maine. Natural items such as bones, moose teeth, shells, stones and earth are incorporated into his paints, often using material from the very scene he is painting.

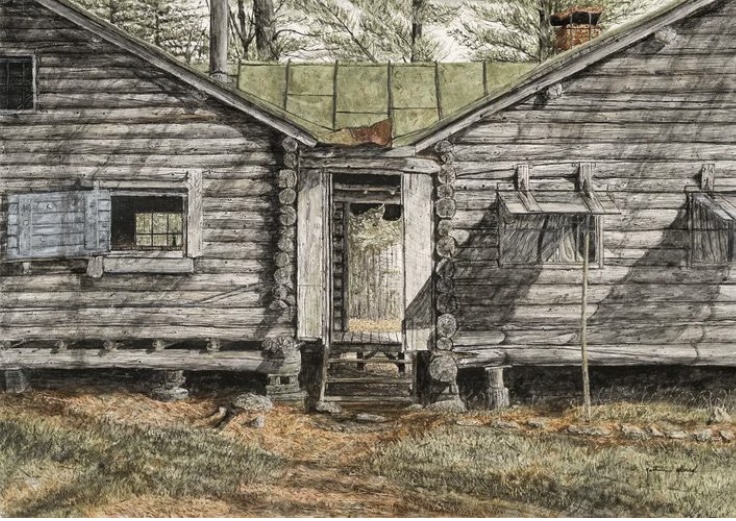

In a print of one of his pieces we bought – “Breezeway” – he used stones from the lake-shore, a charred piece of the cabin, and handmade lead white carbonate to depict the 120-year old log cabin.

Breezeway, Nathan Allard

Nathan’s brushes are made with feather quills from the right wing of the the bird, so that the curve fits over his right hand – as well as with quills from animal furs Allard’s friends bring him. Some come from hunting trips and others from the side of the road. The hair bristles in his brushes are from moose, flying squirrel and other Maine indigenous critters.

Brushes from birds and animals

Friends also supply him with chicken eggs for the yolks he uses in his egg tempera paints and rocks that he grinds. Once the rocks are ground, he mixes the pigments in seashells.

Ground pigments ready to become paint

Working with the natural pigment to make art is an unusual one today, as these materials are usually favored by artists making primitives. He was drawn to egg tempera because of the high level of detail it can achieve, and as we looked through Nathan’s collection of originals and prints, we sensed the simple clarity his techniques produced.

Nathan told us that, after some early experimenting, he decided to take a “cold turkey” approach in his transition to working with natural brushes and pigments. He spoke about the rigorous work ethic all this took, and how his work as a part time timber-framer and five years as a carpenter taught him well about working well. I asked him if he painted mostly from photographs and he said he once did, but recounted how he shifted to painting en plein (French for painting outdoors) about the time he also ditched his plastic brushes and tubes of factory-made paints. We agreed this must entail developing fresh observational skills, and I felt that such skills of seeing within the natural environment went very well with Nathan’s equally natural strategy for sourcing his materials from the scene itself.

Meeting Nathan and seeing his art, learning of his artistic unfolding and of the progression of his techniques left me quite enchanted and fascinated, and in a strange way hopeful. The world of Nathan’s art felt so incredibly far away from our hyper-digital world of TikTok, Facebook, GenAI and the incessant chaos of the 24-hour news cycle. Against that seemingly collapsing world, here in his studio by the lake at the end of a dirt-road in Central Maine, this lovely medieval-like alchemist artist made me happy and hopeful.

Sailboat, Nathan Allard

All I (Thom) could possibly add to my darling Sandy’s loving close, is a tag of pure homage: Nathan has shown us there is an ancient and enduring throughline between the earth we come from and return to, and the art some of us make during the just-long-enough-time we share here.

Our slow-motion move from the away of Philly and New York to the here of Maine has opened us both to an immensity of natural connections, creative energy and love. Art and earth, earth and art – we love how sometimes the difference doesn’t matter, or when creators like Allard makes it unnecessary to tell them apart.

Sandy and Thom – from here, away and places inbetween