Names can bear with them an indelible sin of their history. The settler-colonizers, who confiscated and named all these millions of bountiful acres from the ancient indigenous peoples, double-clutched here on the so-called St. George peninsula. According to the wiki, one of their own conquerors got as far as the western banks of the river they would name St. George and stopped building cabins and forts. For now.

The land to the east and south of where they paused is the land Sandy and I chose to expand our own adventures of love and life and art for as long we’ve got left. The little plot of land we bought and call our own we named Wild Air. As we awaken to late November’s brilliantly distilled chill here amongst the pines and newly naked maples, my imagination turns to the original custodians of this little patch of sublime earth.

The Wabanaki peoples who trapped, fished and lived in concordance in these pine woods and stony beaches for thousands of years before us, caught a rarely afforded break from empire’s juggernaut when the plundering Boston businessman, Samuel Waldo, stopped and turned around in 1736. For almost thirty years, the patent of land “remained unsettled” by European colonizers until the rejuggling of land-takers, law-makers and place-namers following the so-called French and Indian wars of 1763.

Yesterday was the day the settler-colonizers named Thanksgiving in an historical papering-over of their rapacious seizure of these wet woods along the coast. Comrades call it Takesgiving, a re-naming meant to subvert at least a little of White history’s lie. Sandy and I spent the afternoon wandering down the scores of mostly dirt roads which stem off of the three paved roads which entwine amongst the rocks and trees of this peninsula. Most of these rough lanes are posted as private, and warn against us trespassers, some signs, more gently, suggesting that curious interlopers, “turn around here”.

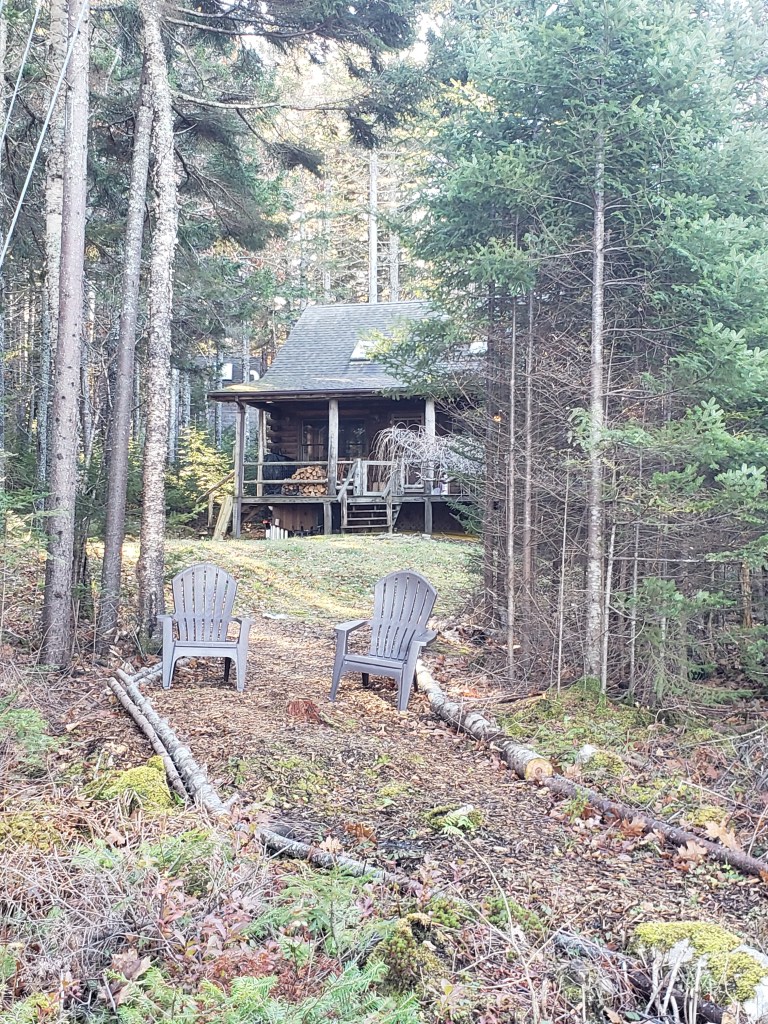

We’re a curious pair and often will continue our slow wanders off the main paths, eager to see the houses and camps sited amongst the pines on the land’s edges. We read the names of families on trees, count the clusters of mailboxes at the entrance of the graveled roads all winding and drawn down to these magnetic shores. We ourselves live on one of these “private roads”, in fact on the corner of two dirt roads, from which, if you turn southward from the northernmost curve, you can look up the sloping land through the wood cut and see our little cabin, the heart of our rough idyll we call Wild Air, after the Emerson fragment.

Our road is privately owned by the people like us who bought or built houses here. Last summer, our first here in so-called Tenants Harbor, we met many of our new neighboring owners at the road association meeting. It’s a quirky assortment of mostly older transplants from ‘away’ as Mainers call anywhere and everywhere else that isn’t ‘here’.

Sandy and I have owned a fair number of houses over the many decades before we met and moved quickly into each others’ lives three years ago. This little acre and half of our Wild Air is actually the second patch of Maine we’ve owned, with the 175 year old cottage in so-called Union being our first. For a supposed anarchist like me, that’s a lot of land ownership which I don’t pretend to defend or to aim to excuse. I have simply come to accept its ambiguous weight as a gift, a product of our love.

My equivocal conscience was just a little eased when we learned at the time of our purchase closing that our access to the sea, the scant but precious twenty-five feet of rocky sea-shore, was actually deeded as an easement. This means the grassy path which winds from across our dirt lane, down to Long Cove through a shaded tunnel of mixed coniferous and deciduous growth, is ours but must be shared, by so-called law.

We dig the more integrative relationship this suggests, between us and wild nature’s geographies, perhaps closer to how the ancient indigenous understood their own symbiotic flow with and for these chilly grounds. Sandy and I are responsible for this mossy slice of public-access land leading down to these infinitely sharable seas. We cut the grass, we clear the falling trees, all to maintain a friendly right of free passage to any and all eager to put in their kayaks with ours, when the tide is highest and most amenable.

Our property is carved from a narrow swath of pine wood, fern-littered moss-covered and sun-filtered even today with temps in the 20s. With the coming winter and fall’s shedding of scattered oak and birch leaves, I noticed a hummock of land I hadn’t before, just above the tiny one-room cottage close to the top of our unmarked property’s edge. I clambered up it yesterday and noticed it was yet another covered-over quarry, a litter of broken and remaindered shards of million-year old granite.

Last summer, I carried two or three at a time, the flatter pieces of granite stones up these sloping woods to piece together a wobbly path above the cottage. Somehow, then, I hadn’t noticed the quarry extended all the way up our hill. All you have to do is scrape a few inches of one-hundred and fifty years of reclaiming loam to see that vast portions of this peninsula were once granite quarries. These badly buried granite quarries are evidence of St. George’s white settler industry of domestic rock mining, the commerce the colonizers turned to after they clear-cut most of this part of so-called Maine to sell as timber to an old Europe who long ago denuded their own woods.

The wiki tells us they sold these cut rocks to build New York and Washington, DC and the felled wood to fuel the furnaces of the slave powered sugar plantations of the Caribbean. That’s a lot of exploitation and appropriation for us to absorb as history’s weight, here amidst the coming winter’s freshening and insistent winds.

I picked my steps carefully back from the cottage last night, through the dark path, stopping twice to look straight up into the almost full November moon. I caught myself, like a child, listening intently for those thousands of years of Wabanaki whispers which must still swirl amidst these ancient cathedrals of spruce and hemlock, especially on such clarifying nights as this…

I find a little weight of history and of names lifted just enough by the sheer wonder of a silvering moon which fills our eyes as we lay our heads down beneath the window of our tiny cabin. Perhaps it is the emancipating sense that there is nothing so-called at the core of our united hearts, a recognition accompanied by our drifting towards a fast and deep sleep, here amidst the lingering whispers of those indigenous who always knew these trees, these rocks and these blackly glimmering seas were the stuff of pure abundance – and most certainly could never be owned by anyone from anywhere.